THE ERA OF FABERGEFor one month this year, Moscow was once again immersed in the essence of Faberge'. Between 20 May and 28 June, the Department of Private Collections of Pushkin Fine Arts Museum held an exhibtion of over 300 objects manufactured by Faberge', the renowned Russian jewellery maker

The collection was on loan from the Link of Times Foundation of Culture and History, and the founder and chairman of its trustee fund is Russian businessman Viktor Vekselberg. In 2004, Mr Vekselberg acquired a Faberge collection that had belonged to American media magnate Malcolm Forbes (1919–1990). This saved the precious objects from going under the hammer and being sold as separate lots and thereby being dispersed among multiple owners. These masterpieces of jeweller's art had been taken out of Russia by nobles fleeing the revolution or sold to foreign collectors in the 1920 to '30s, and now, 80 years later, they have found their way back home.

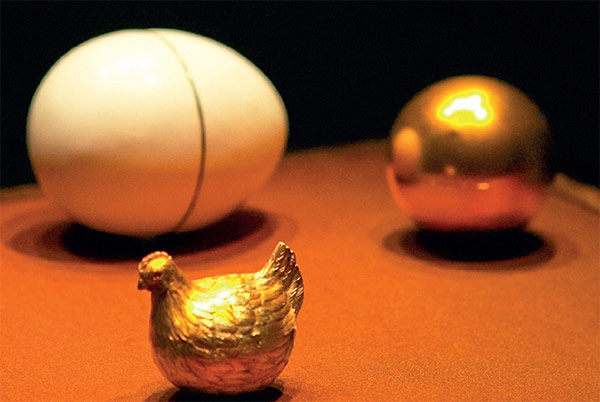

The exhibition showcased landmark pieces produced by Faberge. One such example was the very first Imperial Easter egg, The Hen Egg, which had launched the series of Faberge Easter eggs. The Faberge collection now owned by the Link of Times Foundation is the world's second largest collection of Imperial Easter eggs by Faberge, the first being the collection exhibited in the Armoury Museum in the Kremlin.

The Benvenuto Cellini of the 19th Century

The fin de siecle witnessed the true apogee of Russian jewellery production; it was a time when Russia's jewellers, silversmiths and stone-cutters reached unsurpassed heights in their art. The 1900 World's Fair in Paris proved triumphal for the Russian jewellery school. At the Exhibition, it was the Russian master Karl Gustavovich Faberge was proclaimed the "maestro of modern jewellery art" and awarded with the National Order of the Legion of Honour, France's highest decoration.

Founded in St. Petersburg in 1842 and managed by Karl Faberge from 1872, Faberge company manufactured a wide range of articles, from unique custom-made pieces commissioned by royalty, to mass-produced goods popular among a wider and more ordinary clientele.

Possessing a Faberge was a sign of belonging to the select few, an insignia of sorts. Among the connoisseurs of Faberge's art were not only Russian tsars and dukes, but also the English royal family, King George I of Greece, Baron Leopold de Rothschild and many others.

However, Faberge's recognition was not limited to aristocratic circles alone. For his research and restoration work in the Hermitage, Russia's richest art museum located in St. Petersburg, Faberge enjoyed respect among artists, too. They even hailed him as the "Benvenuto Cellini of the 19th Century."

According to Irina Antonova, Director of Pushkin Fine Arts Museum, Karl Faberge's success is explained by the fact that"his creations are a marriage between high artistry and skilful artisanship. The word "artisanship" should be understood here as it was during the Renaissance, when even the greatest architects, sculptors and artists were recognised for talents through artisans' guilds."

The Easter Series

Easter plays a central part in the Russian Orthodox religion. The tradition of giving Easter eggs as gifts had been observed for centuries. Commoners exchanged ordinary hen eggs dyed with beetroot or patches of colourful calico; wealthy people gave and received eggs made from semi-precious stones, china, glass, papier-mache and bronze. The most popular Easter eggs produced byFabergewere the tiny Easter charm eggs. Made from gold and covered in a wide range of Faberge's famous enamels, they were jewel-incrusted and sported fanciful shapes of rabbits, horse-guardsmen's helmets or baskets.

Back then, there was a tradition for little girls to be given a tiny decorative egg each Easter. It would be fixed onto a gold chain, with a new egg added on each year. By the time the girl was of age, she would have collected an entire Easter egg necklace to wear during Holy Week, as tradition prescribed. The Link of Times Foundation has one such egg necklace among its Faberge pieces.

103rd MERIDIAN EAST, whose logo is a stylised Faberge egg, chatted with Tatiana Muntian, senior staff researcher at the Museums of Moscow Kremlin and consultant to the Foundation, with regard to how exactly Karl Faberge's items came to be synonymous with the Russian elite art:

She says, "The world's creme de la creme viewed pieces manufactured by the Faberge company as perfect gifts to give away or receive. According to the fashion of the time, Faberge's objects were of an eclectic nature, employing elements of the retro style, art-nouveau and the burgeoning art deco. And yet, despite this rather cosmopolitan flavour, Faberge's masterpieces were imprinted with a distinctive Russian tinge. Although the prototype for his famous Easter eggs was of antique French origins, Karl Faberge, a Russian craftsman to the bone, picked up a universal tradition and brought it to perfection."

An Innovator and Perfectionist

Karl Faberge (1846-1920) received a brilliant education in Dresden, Frankfort-on-the-Main, London, Florence and Paris. He demanded a similar profound knowledge of the craft from his staff. Working hours in his company's workshop were long – from 7 am till 11 pm six days a week – except on Sundays when it was open from 8 am till 1 pm. The renowned jeweller demanded the highest quality possible and was said to carry a special hammer in his pocket at all times. If he found a piece manufactured by his employees below his standards, he would smash it with the hammer in front of the staff, despite the cost involved in the production of the unfortunate object.

However, the craftsmen's efforts and their successful works were generously paid off, and their loyalty to the craft was remunerated manifold. Karl Faberge was known to have continued paying salary to a blind 82 year-old stone engraver who had worked in the company for a quarter of a century.

Faberge's success was owed not only to his approach in design and ornamentation, but also to his quick response to technological innovation. Some of his Easter eggs contained rather sophisticated mechanisms, for instance, eggs with clocks inside or the Bay Tree Egg with a tiny mechanical bird that could sing.

Many items from the exhibited collection were not only pieces of jewellery art, but some were also historical documents of sorts. Muntian tells 103rd MERIDIAN EAST about two of them.

The Coronation Egg

One of the most elegant Easter-themed masterpieces by Faberge was the Coronation Egg, which was commissioned in 1897 by the last Russian Emperor Nicholas II as a gift to his wife, Alexandra Feodorovna. It commemorated the couple's one-year coronation anniversary.

This explains why the egg is decorated to look as if wrapped in a gold-brocaded Imperial mantle, which Faberge's jewellers imitated through the use of magnificent translucent guilloche enamel. The egg is encrusted with diamonds, plated Imperial eagles and bay leaf wreaths.

The egg's secret is that it is a miniature copy, true to the very smallest detail, of the carriage in which the young Empress Alexandra Feodorovna rode after the coronation. Built in the 18th century by renowned coach-maker Bukendal for Catherine the Great, the carriage had been involved in every coronation ceremony of Russian tsars ever since. George Stein, one of Faberge's craftsmen, had a rare gift of discerning even the tiniest real diamond from fakes without a magnifying glass. In his memoirs, he wrote that it had taken him over 15 months working 16 hours a day to create the Coronation Egg, a masterpiece of both the art of jewellery-making and that of coach-making.

This is because not only the carriage's exterior was painstakingly imitated – the master went to great lengths to reproduce its gears and rigging, too. The Coronation Egg features carriage springs, a rotatable base, smalls doors on each side that open and a footboard that descends from the inside of the carriage. Its interior boasts armchairs, a canopy and a small ring driven into ceiling. This ring was used for hanging a huge diamond shaped like an Easter egg. The young Empress is believed to have removed the precious stone from the carriage and fixed it onto her Easter egg necklace instead.

The engineering precision of the bejewelled copy of the coronation carriage played the most significant role in the fate of its full-sized original. At some stage, the carriage, which is now on display at the Hermitage, was severely damaged. Within the course of restoration works, the Faberge's Coronation Egg was remembered. Back then, it was part of the Forbes collection. A request for a microfilm with details of the carriage was then sent to New York, and was granted. Thus, a miniature Faberge chef-d'oeuvre helped save another masterpiece by another master from another era.

The Order of St. George Egg

The last Imperial egg was made in 1916 during World War I, when the Russian royal family became separated. Tsar Nicholas II and his son Aleksey stayed at the General Headquarters of the Russian Army. While the Tsar's mother Maria Feodorovna supervised the hospitals of the southern fronts in Kiev, his wife Alexandra Feodorovna and their daughters worked as nurses in makeshift hospitals housed in Tsarskoye Selo, the Imperial residence 26 km away from St. Petersburg, and the Winter Palace.

Keeping in mind that both his wife and mother might expect a traditional Easter egg from him as a gift that year, too, Nicholas II commissioned Faberge to produce two eggs. One of them, the Order of St. George Egg, commemorates Nicholas being awarded the Fourth Class Order of St. George and his son Aleksey with the Medal of St. George. The Order of St. George was issued for not belonging to ruling and noble classes, but for bravery in action. That explained why Tsar Nicholas took immense pride in receiving this award. When arrested by the revolutionists, he managed to hide the award and brought it with him to internal exile in Tobolsk.

The Order of St. George Egg is made from silver and is totally devoid of precious stones. "This is not because Faberge had difficulty with supplies of precious stones and metals during the war," explains Muntian. "Such austere elegance of the Order of St. George Egg can be explained by Faberge's good knowledge of his royal clients, who considered it inappropriate to exchange expensive gifts when the country was at war."

When Maria Feodorovna received this egg, she telegraphed her royal son, who was still at the General Headquarters: "I kiss you thrice and thank you with all my heart for the nice card and charming egg with miniatures. Our old sweet Faberge delivered it personally. It saddens me to be apart... Loving you dearly, your old Mommy." Dowager Empress Maria Feodorovna could not know as yet that her family would never celebrate Easter together ever again...

Natalia Makarova

|

+65 6696 7068

+65 6696 7068

info@meridian103.com

info@meridian103.com

PDA

PDA

+65 6696 7068

+65 6696 7068

info@meridian103.com

info@meridian103.com

PDA

PDA