|

A SINGAPORE TEA PARTY FOR A RUSSIAN TSAR1 His Imperial Highness

On 3 March 1891, Singapore’s daily newspaper The Straits Times received a telegram from the London-based news information agency Reuters. It was in a rush to notify the British colony of the following high-profile event: “It is understood that H. I. .1 the Tzarevitch will land at 4 p. m. to-day”. It was an awfully-short notice that created quite a stir in the languid routine of the tropical island’s high society. Singapore was set abuzz preparing for the welcome of a man who would, in a mere five years, be crowned the Russian Tsar – the last one in history. Singapore was a port of call for Tzarevitch Nicholas who was on a voyage from Trieste to Japan and then Vladivostok. The purpose of the royal offspring’s journey to the East was to back up diplomatic relations in every country visited, as well as to fill in the gaps of his home schooling.

Combining Business with Pleasure the oyal Way

In 1890, Russian Tsar Alexander III decided to launch the Great Siberian Railway whose construction was supposed to begin from Russia’s Far East: Vladivostok. To emphasise the significance of this undertaking for the Russian Empire, the Tsar wished for his son, Tzarevitch Nicholas, to be present in person at the ceremony of the start of construction, where the latter would push a symbolical wheelbarrow of soil for the road-building. Due to royal regulations prescribed for a royal to never travel the same route twice, it was decided that Nicholas would reach Vladivostok by sea and return to St. Petersburg by land – via Siberia.

It was agreed that Nicholas’ younger brother, Tzarevtich George, who had a lung condition, would go on the journey, too, to take advantage of the salt-saturated sea air. The voyage, which lasted from 23 October 1890 to 4 August 1891, was viewed somewhat as a self-enrichment course: both brothers were to find out more about the Eastern lands and try their hand at diplomacy, backing up old and setting up new relations with their rulers along the way. The empress also wished for her older son to clear his mind, as he was preoccupied with two women at once: ballerina Matilda Kshesinskaya, his mistress, and German Princess Alice Hessen-Darmstad (who would later become his wife and take the Russian name of Maria Feodorovna).

First, Nicholas and George headed for Athens where they were joined by another George, their cousin and heir of the King of Greece. But the actual sea voyage set forth from Trieste, where the three princes and their entourage embarked on the semi-armoured frigate Pamiat Azova (Memory of Azov). One of the young Russian aristocrats accompanying Nicholas was Esper Ukhtomsky, who would later publish a three-tome book about this Eastern voyage. A great deal of photographs was taken during the trip by Vladimir Mendeleyev, son of the renowned chemist Dmitry Mendeleyev and warrant officer of the Pamiat Azova. About 200 photos of his have survived to date.

In the Land of Rajas, Tigers and Red Coats

From 10 to 27 November, the Pamiat Azova was anchored in the roads of Port Said, and the two weeks were spent getting Tzarevitch Nicholas acquainted with Egypt – he floated down the Nile River and climbed the pyramids. After this, the Russian ships travelled from Suez to India and, on 11 December, arrived in Bombay. Nicholas and his entourage landed and undertook a three-weeks trip by land around India, visiting Agra, Lahore, Amritsar, Benares, Calcutta, Madras and Colombo (Ceylon). There, Nicholas went sightseeing, met with the rajas, bought artworks from local artisans and even went hunting – but he was unlucky and did not take home any trophies, while two princes from his entourage, Bariatinsky and Obolensky, shot one tiger each.

This couldn’t but further dampen the Tzarevitch’s already low mood, which was the result of the extreme heat and the “red coats” (the British), the sight of whom suffocated him, according to Nicholas. They reminded him of the strained relations between Britain and Russia of that period. Empress Maria Feodorovna rushed to reply to her son’s letter: “I would like to think that you are polite with all the Englishmen who are doing their best to receive you arranging receptions, hunting, etc. for you. I am well aware of the fact that balls and other official ceremonies bring no pleasure, especially in the heat, but you must understand that your position imposes a high responsibility on you. Forget about your personal convenience <…> and remember of my only wish, which is for you to leave the best impression on everyone, everywhere.”

The Indian stopover marked the midway point of the Eastern voyage and, unfortunately, deprived Nicolas of his brother’s company. Tzarevitch George Alexandrovich had been suffering from fits of cough and fever, so his royal parents demanded that he return to Russia to the salubrious air of the Caucasus Mountains. Therefore, when the Pamiat Azova left Bombay taking Nicholas and the other George – the Prince of Greece – further eastwards, George Alexandrovich embarked on a Russian ship headed in the opposite direction – to Russia.

The Singapore Tea Party

Singaporean high society found out about the royal visit from The Straits Times on 3 March 1891. However, we must remember that the British were using the Gregorian calendar, while the Russians were still sticking to the old-style Julian calendar, with 12 days difference between them. Having said that, we now know that Nicholas was in Singapore from 19 to 21 February 1891, which is in line with the rest of the dates given here in the old style.

The preparations undertaken to welcome the high-positioned guests are best described by a reporter from The Straits Times:

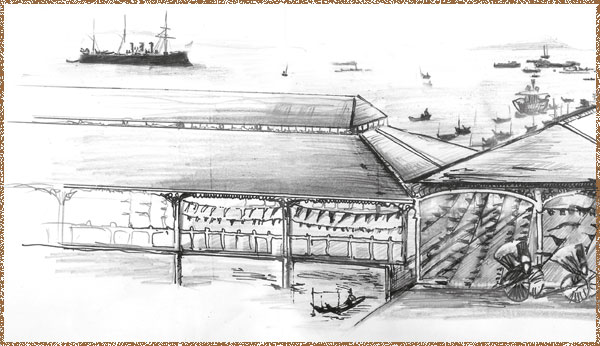

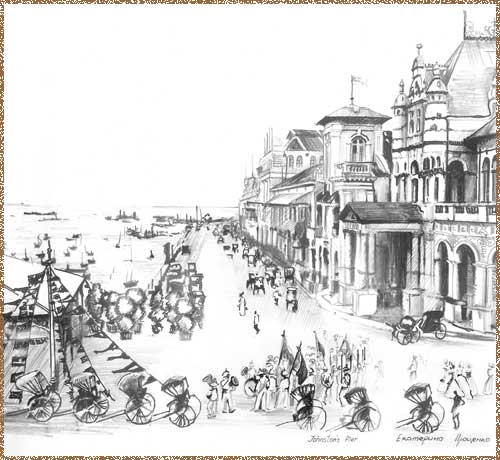

“ <…>The order then went forth to make the best possible preparation for the fitting reception of H. I. . and a late hour intimation was given to the authorities at the Shipping Office to get Johnston’s Pier in readiness. Boarding Officers were at once set to work, and in the small hours of the morning handcarts, rickshaws and other conveyance were running hither and thither getting greenstuffs, and bunting, and wherewithal to make Johnston’s Pier look pretty. What last night was a common ordinary structure without the faintest sign of decoration has suddenly been transformed into a graceful and attractive reception hall. The roof of the portico has been lined with an arrangement of British and Colonial ensigns forming a very pleasant canopy. The entire pier is adorned with all sorts of bunting neatly arranged and tastefully interwoven with refreshing greenery. <…> there is draped, with some skill, the different flags of Russia and (as a mark of respect to the son of the King of Greece who is with H. I. .) the flags of Greece, intermingled with the flags of the Colony. <…>”

The next-day’s piece of reporting described the actual visit and those present at Johnston’s Pier, Singapore’s then main landing spot:

“ … Amongst those present were <…> members of the Executive Council…, all of whom were in the morning dress of civilized civilian society, or as near it as the resources of their wardrobes, or the distance of their houses from town, rendered practicable at short notice… None of the Consular Corps were present, and indeed, the H. I. . has expressed the desire that there should be as few people as possible.

The Russian Consul was early on the scene and when H. . the Governor, who was in uniform with the star of the Order of St. ichael and St. George on his breast, arrived shortly before 4 ’clock, he was received by the Consul. Shortly after 4 o’clock, saluting commenced from HMS Caroline… denoting that H. I. . has left his ship Pamiat Azova. A few minutes afterwards the steam launch containing H. I. . and suite came alongside the pier. H. . the Governor and the Russian Consul received H. I. . as he landed on the pier.

H. I. . was accompanied by Prince George and Prince Bariotinsky… The royal party were given the customary salute by the guard of honour, while the band played the Russian National Air…

H. I. . ’s stay at the Government House was brief. They had afternoon tea. Shortly after 5 o’clock H. I. . with the Governor returned to the pier.”

The Straits Times also was aware of Nicholas’ plans following his short visit to Singapore:

“On Tuesdays morning H. I. . will leave with the fleet for Batavia. It is, we are informed, the intention of H. I. . to remain no less than 7 days in Java, during which time H. I. . will be the guest of the Governor-General at Buitenzorg. … H. I. . has accepted the proposed services of the Netherlands steamer Lucifer to assist in the navigating of the Russian ships to Batavia.”

Neptune Day Celebration

for the Tzarevitch

After visiting Singapore, the Russian ships arrived in Batavia, capital of the Dutch East Indies back then and today’s Jakarta, and found themselves in the Southern hemisphere. This detour was done on purpose: for the Tzarevitch to cross the equator and commemorate this event by celebrating Neptune Day (a party thrown for those crossing the imaginative line of the equator for the first time in their lives, which was a Russian naval tradition). The entourage was disguised in various costumes, their faces colourfully painted, with one of the crew pretending to be Neptune, the King of the Sea. The party culminated in a swimming session in a makeshift pool made of sailcloth.

Bangkok was the next stop, where Nicholas paid a week’s visit to the Siamese king, Rama V Chulalongkorn. Then the ships called in Nanking, China’s ancient southern capital, from where the Vladivostok steamboat took them down the Yangtze River to the town of Hankow. A large tea factory belonging to the Russian firm, Tokmakov, Molotkov and Co., was situated there. It was Russia’s largest supplier of Chinese teas.

The Otsu Incident

At last, by mid-April 1891, the six Russian ships arrived in Japan, the final foreign destination of the sea voyage. Few know that the visit nearly cost the future Russian Tsar his life. One day, when returning to Kyoto from sightseeing, Nicholas and George of Greece were riding in a rickshaw’s open carriage. Suddenly, from the crowd of Japanese townsfolk bowing in respect, a policeman on guard duty, named Tsuda Sanzo, stepped forward and hit Nicholas with a samurai sword on his head, twice. Blood appeared but the wound was minor. Another blow followed, but George parried it with his cane. Tsuda Sanzo was quickly knocked down and tied up by two rickshaw drivers.

The attempted murder was called the Otsu Incident after the name of the city in the Shiga Prefecture where it occurred. Fortunately for both countries, there was no drastic aftermath of the incident – not for another 13 years, at least, when Japan attacked Russia, launching the Russo-Japanese war. According to Ukhtomsky’s account, Nicholas did not take the situation seriously, and all he said was: “It is nothing. I only wish for the Japanese not to think that this incident could ever change my feelings for them and my gratitude for their hospitality.” The Tzarevitch personally awarded the rickshaw drivers with the Order of St. Anna.

After Nicholas left Kobe on 7 May 1891, he arrived in Vladivostok four days later and, as planned, opened the construction site of the Great Siberian Railway by laying the foundation stone of the Vladivostok railway station. On 20 May, the Tzarevitch ceremoniously bid farewell to the crew of the Pamiat Azova and the rest of the ships, and went back to St. Petersburg overland via Siberia, arriving home on 4 ugust 1891.

The Writings of Esper Ukhtomsky

The Eastern tour of the future Russian Tsar was immortalised in history by Esper Ukhtomsky, who accompanied Nicholas throughout his travels. The first tome of his book, Travels in the East of Nicholas II, Emperor of Russia When Cesarewitch 1890–1891, was published in 1893. Two other tomes were published in 1895 and 1897. All three tomes were immediately translated into English, German and French. In his impeccable literary language, Ukhtomsky described the history, religions and everyday life of Eastern peoples. Upon returning from the voyage, Ukhtomsky was nominated a member of the National Geographic Society. The success of his books owed much to the multiple (about 700) illustrations by N.Karazine, an artist, ethnographer and traveller.

“Shaking the Fist at England from Around

the Corner”

The Pamiat Azova was not the only ship to accompany Tzarevitch Nicholas. Russians are prone to showiness, and the journey to the East was one such example. The Russian squadron plying the waters of the Southern Seas dazzled each and every one with the number and class of its ships. Their variety was not so much to match the royal entourage’s status, but to threaten the world and evoke respect for the Northern Empire. There is a self-explanatory passage from the book The Semi-Armoured Frigate Pamiat Azova 1885–1925 by R. M. elnikov, under the chapter: “Under the Heir’s Banner”.

“The pompousness of this wild travel was decided <…> to be enhanced by joining the whole of the Pacific squadron to the Tzarevitch’s ships en route… In addition to the two gunboats, the Admiral Nakhimov, the then most powerful battle cruiser, was brought over from Nagasaki via Manila to Singapore. It was meant to pay respect to the Tzarevitch personally and to beef up the royal convoy… The cruiser had come to Singapore before Nicholas as soon as news of his arrival was received, in time to prepare for his grand reception.

On 18 February, after the Pamiat Azova and the Vladimir Monomakh behind it anchored in the roads of Singapore, all the ships, both Russian and foreign, fired the salute of 25 salvoes and sent their crews up the masts who shouted the quintuple “Hurray!” <…> ‘This splendid welcome and the joining of the squadrons were not void of a certain magnificence, which, it seemed, was not much liked by the British’ (The Naval Digest, 1916, Issue 6, p. 41). It was clear as the day that this play of petty ambitions, nicknamed by officers as ‘shaking the fist at England from around the corner’, did not justify the expenses wasted on bringing the Admiral Nakhimov from Japan to Singapore…”

An Expert’s Commentary

Galina T. Tyun

(Associate Professor at the Faculty of istory of Far Eastern Countries, St. Petersburg State University, Russia)

Tzarevitch Nicholas’ travels to the East have always drawn attention from historians, Orientalists and political scientists. This may be generally explained by the enhanced interest in the personality of the last Russian Tsar and the era of severe confrontation of the world’s leading powers and the escalating contradictions, which led to the unleashing of World War I. Additionally, interest was stirred up by the public’s curiosity about the countries of the Southern Seas and the exoticism of the Tzarevitch’s journey, details of which were beautifully rendered in Ukhtomsky’s books. These became part and parcel of any Russian aristocrat’s library and played a significant role in the public’s education.

At the end of the 19th century, the attitude to the Eastern travels was somewhat ironical because of their wild scale. However, history knows numerous analogous examples of such interactions between belligerent countries at various times.

Sources: A.I.Teryukov, Ph.D. Travels in the East: The Unique Exhibition Dedicated to the Travels in the East of Nicholas II, Emperor of Russia When Cesarevitch 1890–1891, from St. Petersburg to Japan and via Siberia. (http://www.kunstkamera.ru/exhibitions/na_vystavkah_v_drugih_muzeyah/arhiv/puteshestvie_na_vostok/)

By Julia Sherstyuk

|

|

+65 6696 7068

+65 6696 7068

info@meridian103.com

info@meridian103.com

PDA

PDA

+65 6696 7068

+65 6696 7068

info@meridian103.com

info@meridian103.com

PDA

PDA