WILLIAM FARQUHAR: THE FIRST RESIDENT OF SINGAPORE The May of 1839 was no different than last year's: here in Scotland, it had

always been a month when the weather finally settled, marking the cyclical

change from the gloom of winter to the buoyancy of summer. The sun was

generously spilling its rays over a large Georgian house as if trying to warm

up its walls, clammy from the late night frost. Some bolder sunbeams ventured

through the sash-window and landed on the face of a man in his late sixties,

sitting in front of a black marble fireplace lit by obliging servants. Their

warmth-loving master had spent 30 years in the Asian tropics and had been once

referred to – unofficially, though – as the Raja of Malacca...

The May of 1839 was no different than last year's: here in Scotland, it had

always been a month when the weather finally settled, marking the cyclical

change from the gloom of winter to the buoyancy of summer. The sun was

generously spilling its rays over a large Georgian house as if trying to warm

up its walls, clammy from the late night frost. Some bolder sunbeams ventured

through the sash-window and landed on the face of a man in his late sixties,

sitting in front of a black marble fireplace lit by obliging servants. Their

warmth-loving master had spent 30 years in the Asian tropics and had been once

referred to – unofficially, though – as the Raja of Malacca...

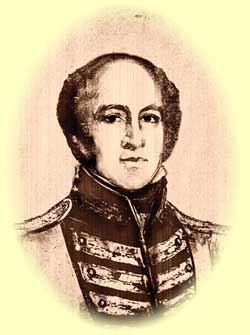

...William Farquhar, a descendant of the ancient Scottish clan of

Farquhar –

(meaning “honest” or “beloved man” in

Gaelic) – had lived up tohis forefathers' name. True to the chosen path of a British soldier, he won

andenjoyed the genuine respect

of those around him, regardless of the race or

status. His was a life full of adventures, discovery, diplomatic games,

friendship, love and betrayal.

His career began at the East India Company, initially a commercial trading

company that over time became a virtual ruler

of India and some Asian colonies.

Several years later, young Farquhar took part in a military expedition against

Dutch-held Malacca, was gradually promoted and finally appointed Resident and

Commandant of Malacca, one of the oldest and most powerful Malay sultanates

that owed its wealth to its trading port. Farquhar supervised both civil and

military offices there after the state had passed into British hands from the

Dutch.

The time he spent in Malacca was probably the happiest in his life... The

young and inquisitive official was entirely fascinated with the brave new

world of the sultanate, which was incredibly rich in history and imprinted with the

strong European influences of its previous conquerors. He busied himself

learning the Malay language and local customs,

and lived as man and wife with

a local girl, Antoinette Clement, the Malaysian daughter of a French officer,

with whom he had six children by her.

Fascinated by the tropical wildlife and natural history, Farquhar sent

servants to collect plant and animal specimens,

later commissioning artists

to paint the findings. The paintings comprised one of the best art collections of tropical

nature, worthy of being donated to the Royal Asiatic Society in London. When

ordered by the British government to demolish all Dutch-built structures in

Malacca, Farquhar engaged his diplomatic skills and persuaded the officials to

change their minds. Why blow up solid fortifications and holy places like

Christ Church that could still be of service and impart character

to the state that had become his new home?

However, as a loyal servant to the British crown,

However, as a loyal servant to the British crown,

he was hardly ever a man of

free will. Instead, he was

a part of incessant political games to expand the

empire

at the expense of other lands... They changed the destiny of a nation

and his life... In 1818, he was forced to leave Malacca, his home of 15 years; it

had been handed back to the Dutch in compliance with the Treaty of London. Just

a pawn in a political game between two powerful empires thirsty for colonial

expansion, Britain and the Netherlands, Farquhar was about to set sail back

to Scotland.

But fate seemed to have other plans for the former

“Raja of Malacca”. Aware of

Farquhar's long Malayan experience, the British authorities ordered him to

assist Stamford Raffles, then Lieutenant-General of Bencoolen, the pepper

trading centre established by the British on Sumatra 200 years before, to

found a new settlement in the region. This settlement would later drive a wedge

between the two British officials...

...The old man opened his eyes, woken by a clanking sound. A servant

brought in a silver tea tray and was now serving tea, its rich amber

glistening when poured into a fine cup of bone china. Farquhar grinned: those two things

– chinaware and tea – were now taken for granted in Britain. And he, a mere

cog in the mammoth machine of the East India Company, had helped bring them to

Britain, along with other much-coveted Asian goods: cotton, silk, indigo dye,

opium and spices...

...Britain, striving to ensure lucrative trade with China, to watch closely

every move of the Dutch after they had gotten Malacca back, and to secure a passage

from India to the Chinese sea, desperately needed a new settlement in the

Malay Archipelago. Both Bencoolen and Penang were too remote. A new trading post

south of the Malaccan Straits was vital

for the British Empire.

After a brief survey of a number of islands, no Dutch presence was

established on the island of Singapore, about 200 miles south of Malacca.

Back then, Singapore belonged to a Malay ruler, Hussain Shah, who, in the tradition of

maritime Malay sultans, collected taxes and received tributes from the

captains of Asian trading vessels calling at his port. The island was also controlled

by a Malay temenggong (chief of police), Abdul Rahman. Raffles and Farquhar were

facing a challenging task of winning over the two men and gaining their

consent to cede the strategically advantageous island to Britain.

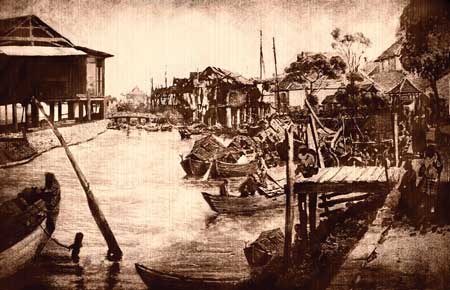

28 January, 1819. It was about four in the afternoon, the heat subsiding,

the day slowly yielding to the early tropical night. Several ships, with two

Englishmen aboard one of them, anchored about half a mile off the mouth of the

Singapore River. Sprawling along the coastline, there was a Malay village.

Farquhar was immediately taken by the serenity and simplicity

of the landscape,

so different from the hustle and bustle of Malacca. A few goods-carrying,

mat-sheltered sampans and light fishing koleks were floating idly on the calm

waters; some Malay boys were playing among the giant coconut trees;

a pungent smell of sun-dried fish was filling the air. Behind the temenggong's village

was nothing but boundless uninhabited virgin jungle.

The following morning, Farquhar and Raffles came ashore. To show their

peaceful intentions, they brought with them only one sepoy carrying a musket. At

the temenggong's house, they were expected and welcome. The swarthy face of the

local chief wreathed into a smile, his hands holding a wooden platter heavy

with rambutans and other local fruits. Raffles led the negotiations

The following morning, Farquhar and Raffles came ashore. To show their

peaceful intentions, they brought with them only one sepoy carrying a musket. At

the temenggong's house, they were expected and welcome. The swarthy face of the

local chief wreathed into a smile, his hands holding a wooden platter heavy

with rambutans and other local fruits. Raffles led the negotiations

in Malay. He expressed the wish for Singapore to become

a British trading port and

explained how the trade would help the inhabitants. Besides, both the Sultan

and

the temenggong could count on generous annual rents

of 5,000 and 3,000 Spanish dollars respectively.

The two Malay rulers were not to let the cash slip away and, on 6 February

1819, both the Sultan and the temenggong signed a treaty with Raffles, which

granted the East India Company permission to establish a “trading

factory” in Singapore. It would take another five years and another treaty

for Singapore to

officially become a British colony. In the meantime, the historic deal was

sealed with a sumptuous banquet, during which gifts – mostly opium and

arms - were exchanged and the Union Jack was hoisted.

The next day, Raffles appointed Farquhar the First British Resident and

Commandant of Singapore and instructed him, before sailing back to Bencoolen,

to develop the settlement in accordance with his own specific plan, a plan

which would later become the stumbling block in Raffles and Farquhar's

relations...

In his new position, Farquhar faced serious challenges which Raffles had

never taken into consideration. Having proclaimed Singapore a free port, Raffles

exempted merchant ships from all sorts of taxes: import and export duties,

tonnage, port

and anchorage duties and port clearance fees. No doubt, it

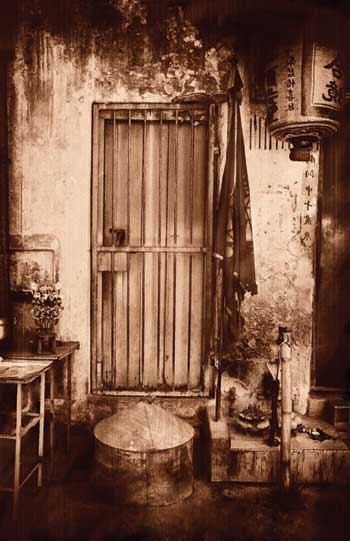

proved extremely attractive to Chinese merchants who had

to pay high duties in

Dutch-controlled ports, but for Farquhar, it was a recipe for disaster.

The lack of revenue meant having to carry our Raffles' ambitious plans on a

shoestring. Farquhar turned to the senior officers in Calcutta for help,

but they were not inclined to invest in public works. He had no choice but to

pay for a number of expenses out of his own pocket. Raffles was of no assistance,

either. Stationed in the West Sumatra, he was unable to tend to urgent

matters

due to a poor postal service.

Out of despair, Farquhar resorted to revenue farming - he auctioned

monopoly rights from the state for the operation

of gambling dens and the sale of

arrack and opium. Cockfighting, gambling and the slave trade as licensed activities

ensured a much-needed cash flow.

... Some memories were pleasing and warming, like the hot tea he was

sipping. Indeed, he had a right to be proud - it was he who, against heavy odds and in

a mere four months, transformed a rural Malay settlement into a busy

cosmopolitan town. Many Asian merchants, knowing him to be a wise and reliable man from his

earlier Asian period, took up his invitation to come to Singapore and start

new businesses there. Indigenous sampans and koleks soon looked like tiny

splinters when passed by Chinese junks with their arched sides, frigates, schooners and

sloops calling at Singapore.

The range of goods they were carrying was

enormous: silk and porcelain from China, hemp from the Philippines,

cotton and dyes from India, rice and spices from Indonesia...

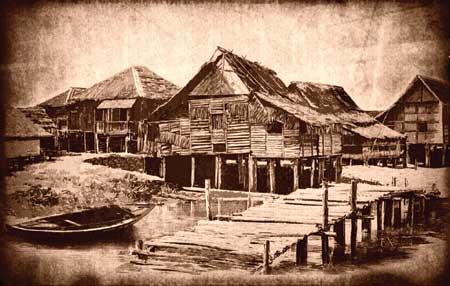

...Under his direction, impenetrable jungle game way ...Under his direction, impenetrable jungle game way

to new timber houses with

traditional Malay attap roofs and open verandas; wide roads, including High

Street where Farquhar built his residence, were being laid. Pepper, cocoanuts,

pineapple, nutmeg and gambier trees were grown by an expanding Chinese

community.

It was he who successfully brought a major threat

to Singapore's settlers – rats under control. Incredibly huge and ferocious, they were

reported to have attacked cats that initially were the only hope of wiping the

rodents off the island. Offering commoners a shilling for every rat caught

helped rid Singapore of the pests in a fortnight and once again consolidated

Farquhar's reputation as a wise administrator.

By the end of 1820, Singapore's trade had already exceeded that of Malacca

during its most prosperous period.

The number of Singapore's inhabitants grew

from 200 to over 6,000 and kept rising. The Dutch were incensed

by the strengthening position of Britain in the region. Thyssen, the Dutch Governor

of Malacca, even threatened

to sail to Singapore and bring Farquhar back in

chains. A professional soldier, Farquhar had first-hand knowledge

of a settlement defences and had a fort built behind the Malay village,

strategically positioning it right by a freshwater creek. He was determined

to repulse any enemy, despite having only 340 men and 12 guns at his

disposal.

Delighted with the settlement's rapid transformations, Raffles was

nonetheless furious at many aspects of Farquhar's administration whose desperate

measures – allowing gambling dens and slavery - outraged Bencoolen's

Governor

as disgraceful and vice-encouraging. But what angered Raffles most

was that Farquhar allowed to build houses

and godowns on the north bank of the

Singapore River which he had set aside for governmental use. Raffles had

allocated the Beach Road area to merchants who later complained to Farquhar

that it was low, swampy and subject to continual surf, which made the ground

unsuitable for either erecting buildings or landing goods from ships. To

Farquhar, the development of the commercial district was a priority over a

Government House, so he let the merchants have the reserved plots.

Having to act under the immediate supervision of a younger man, a junior

official at that, who failed to understand

the actual situation, was frustrating for Farquhar. Tensions had been growing and, on 28 April 1823, the

differences between the two came to a head - Raffles dismissed Farquhar as

Resident “with effect from 1 May”. Three weeks later, Farquhar was

removed as Commandant, too...

Humiliated and bitter at the dismissal, Farquhar stayed on the island till

the end of 1823. At a farewell dinner, Farquhar was presented with a large

silver epergne,

Humiliated and bitter at the dismissal, Farquhar stayed on the island till

the end of 1823. At a farewell dinner, Farquhar was presented with a large

silver epergne,

the commissioned work of London silversmiths –

a gesture of never-ending respect and admiration from

the local communities. On his day of

departure, as later reported by a Calcutta newspaper, a motley crowd

of Singapore's inhabitants, both European and Asian, accompanied their

ex-Commandant to the beach,

with the troops forming a guard-of-honour from his

house to the landing place. Singapore's First Resident embarked under the

sounds of salute customary to his rank. Numerous boats accompanied him to his

ship, the Alexander, and as they sailed, some of the Siamese vessels fired

salutes in his honour...

...He could not help but think that the major difference between the two of

them was of a personal nature. The two men were no total strangers, having

participated in the same missions and shared a genuine affection for the

Malays. However, Raffles felt that the white man had o keep a certain distance

from the locals, and he was not beneath laughing at Farquhar's local family,

whom he archly called a “Malay connexion”. Prim and proper and

convinced that he was always right, Raffles reported Farquhar as having moved away from

“the usual etiquette in dispensing with the military dress of his rank,”

when he found out about the Commandant's new habit of wearing a sarong...

...The old man moved his eyes from the fanciful dance of the flames. The

servant gone and the table cleared, he was now once again alone with his thoughts.

The ancient maxim was wrong: time had proved a poor healer. It had failed to

soothe the pain of insult inflicted by Stamford Raffles. Sensing that the bygone

grievance was about to rekindle, Farquhar pulled the plaid up to his chin,

seeking comfort in its warmth. But it brought him little relieve, as his

treacherous mind kept taking him 16 years back, evoking his own letter to

Raffles, written in the nervous hand of a hardened soldier wrongfully

dismissed:

«...Nothing has been wanting on my part to advance the prosperity of

this Settlement by every means in my power,

that our Political and Commercial

relations with all the surrounding Native States throughout the Eastern

Archipelago,

the Malay Peninsula, the Eastern coast of Sumatra, together with

the kingdoms of Siam, Cambojia and Cochin China, have been supported,

cultivated and improved, both by extensive epistolatary correspondence as well

as every other suitable and available means within my reach... the

establishment generally during the period I have had the honour

to direct

its affairs, has attained to a height in population, wealth and general prosperity I may

venture to say quite unrivalled.»

A rather muddled and lengthy letter, aimed to reach out to Raffles'

conscience, and failing to do so, a cry from his heart that was never

heard... It was followed by Farquhar's statement to the Court of Directors of the East

India Company, in which he requested his rightful reinstatement and asserted his

right as the founder of Singapore. It bore no fruit except to get him promoted

to the rank of Major-General. What a measly compensation for everything he had

done for Singapore! A rather muddled and lengthy letter, aimed to reach out to Raffles'

conscience, and failing to do so, a cry from his heart that was never

heard... It was followed by Farquhar's statement to the Court of Directors of the East

India Company, in which he requested his rightful reinstatement and asserted his

right as the founder of Singapore. It bore no fruit except to get him promoted

to the rank of Major-General. What a measly compensation for everything he had

done for Singapore!

...How many times did he try to keep his charging at bay and not argue with

the late antagonist (Raffles had died three years after dismissing Farquhar). That

Raffles was a visionary Farquhar had never failed

to admit. And yet, while

describing Singapore as “his Child” and

“his

Colony”, Raffles could have at

least admitted his, Farquhar's role

of a doting mother who had nursed the

infant settlement during its first four years...The old man got off the chair

with difficulty and stepped out into the garden that was preparing to burst

into blooming in a matter of days. The changing of the seasons – that was

what he had missed most while residing in the eternal summer of Malacca and

Singapore. He smiled and walked pensively down the cobbled path, unaware

of that that May would be his last...

... Farquhar died on 11 May 1839. He parted this world, never reconciled

with his role as Raffles' assistant in forming the settlement

of Singapore. His tombstone's inscription reads the following:

“...During 20 years of his

valuable life he was appointed to offices of high responsibility under the civil

government of India having in addition to his military duties served

as Resident in Malacca and afterwards at Singapore which later

settlement

he founded...”by Julia Sherstyuk

|  +65 6696 7068

+65 6696 7068

info@meridian103.com

info@meridian103.com

PDA

PDA

+65 6696 7068

+65 6696 7068

info@meridian103.com

info@meridian103.com

PDA

PDA