A PLEA FOR SAMOVAR TEAAs part of a series showcasing Russian food and traditions, Singaporean Edwin Yeo Jiong Ning, who is genuinely in love with Russian culture, discusses the great tradition of the Russian tea party.

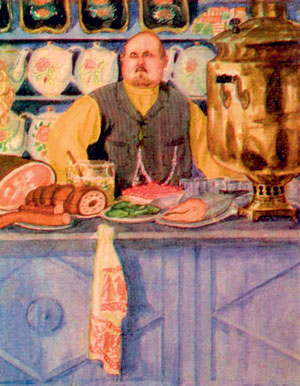

Great mystery surrounds the Russian samovar. This is especially so for foreign readers of Russian literature since they have, most certainly, on more than one occasion, found themselves perplexed and bewildered by the alien word "samovar" in great literary works, such as Ivan Turgenev's Fathers and Sons, where heated philosophical debates between Bazarov and others often took place during samovar tea sessions. Hence, it is obvious that the samovar is a highly influential cultural entity, but what exactly is it?

Ambiguous Origins, Russian Identity

A samovar is a metal container used for heating water and making tea. The name "samovar", literally translated as "self-boiler", derives from two Russian words: "sam" meaning "itself " and "varit" meaning "to boil".

With regards to where and how samovars originally came from, there are many competing schools of thought. One account states that samovars were first built in Tula, a town around 150 km away from Moscow, by the Lisitsyn brothers in 1778.

Eternally famed for having produced the first samovar in Russia, Tula today is the undisputed samovar capital of Russia, boasting numerous samovar factories equipped with state-of-the-art tools to push the conventional aesthetic appeal of samovars to new heights.

Other accounts, however, prove otherwise, such as the legend of Peter the Great who carried the first samovar to Russia from Holland. Though there is apparent confusion over the true origins of the samovar, whether samovars were truly a Russian creation did not matter since Russians readily embraced the device as part of their daily lives and national identity. In this sense, Russians made samovars Russian. The leading architect was the great Russian poet Alexander Pushkin. His works are full of rich descriptions of the everyday habit of tea-drinking among the Russian upper classes, and were among the first to establish the ritual of chaepitie (tea-drinking accompanied by various desserts and friendly conversation) in the Russian national consciousness.

"Where There is Tea, There is Paradise"

Samovar tea tastes different from conventional tea not because of the use of special tea leaves. It has more to do with the method, which involves brewing a concentrated tea solution, zavarka, in a teapot, to be placed on top of the samovar. After this, the concentrate is to fill up only around one-third or onequarter of the cup, which is then in turn diluted with hot water from the samovar itself. Tea made via the samovar way tastes stronger and is more potent than the conventional method.

The samovar tea-drinking experience, chaepitie, is also one that is highly unique. Samovar tea sessions are synonymous with warmth and cosiness. This is especially so when people crowd around the pipinghot samovar during cold and harsh Russian winter days. Samovars warm peoples' hearts and open up their souls. These are the times when most of Russia's literary heroes spar their wits with others or when people engage in serious conversation. Such an experience is similar to that of the Japanese or Chinese tea-drinking culture, involving not just tea-drinking, but socialising elements as well. Through samovar sessions, friendships, camaraderie and strong family ties are born. Hence, the samovar goes way beyond just tea appreciation; it is the key ingredient for one to understand the quintessential Russian soul.

I recall an experience where I was out in the parks of St. Petersburg during the Maslenitsa (Shrovetide) celebrations. Despite being sufficiently armed with thick jackets, enduring the harsh, cold Russian wind was still unbearable. Just when I was considering calling it an early day, I caught sight of the unmistakable samovar steam puffing away in the distance, and the discovery was, to some extent, akin to finding an oasis in the desert! In that instant, I understood why samovars were highly prized in Russia. A cup of simple chai next to the warm samovar in wintertime was priceless, just like the old Russian saying, "Where there is tea, there is paradise."

Cultural Ambassadors that Puff

Even if samovars were not originally the creations of Russians, they were definitely the ones who made the samovar culture big and international. Samovars were seen as the ambassadors of Russian culture and traditions – hospitality and warmth. However, there is a certain fear that this great tradition is slowly starting to lose its influence within Russia itself. Victor Pelevin, the literary zeitgeist of Russia in post-Soviet times, stated this in the opening line of his famous novel, Generation P: "Once upon a time in Russia, there really was a carefree, youthful generation that smiled in joy at the summer, the sea and the sun and chose Pepsi." Though this should not be understood literally as Russians choosing Pepsi as their new favourite drink in place of tea, it reflects a new generation that seems ready to abandon historical and cultural aspects of its tradition and embrace everything modern or Western.

This seems evident in Russia today where samovars are increasingly seen as less relevant, relegated to historical exhibits in museums. Samovars are also seen as an object of tourists' Russian imagination. Urban Russians seem to be all too ready to exchange slow yet aromatic cups of samovar tea for the convenience of instant tea bags. My hozaika (landlady) is one, for example, who piles heaps of sugar into her chai made from tea bags, to which I exclaimed in horror, "Eto ne chai; eto sladkaya voda!" ("This is not tea; it is sugar water!") Russia has made a great contribution in terms of global tea appreciation culture. It would really be a waste and pity if the great samovar journey were to end here. The great samovar tea culture is especially significant to Russia as it undergoes its post-Soviet hangover. A fine cup of samovar tea rewards one's patience with both a delightful taste and a warm, cosy communal tea experience, one which is impossible to get from an instant tea bag. This is something that Russians have created of which they should be very proud.

Text Edwin Yeo Jiong Ning

Photos 103rd Meridian East

|

+65 6696 7068

+65 6696 7068

info@meridian103.com

info@meridian103.com

PDA

PDA

+65 6696 7068

+65 6696 7068

info@meridian103.com

info@meridian103.com

PDA

PDA